Researching nothingness is certainly more difficult than one might think. During my desktop research I came across a few interesting publications. Firstly, there is The Book of Nothing by John D. Barrow, which captures the mysteries of non-existence, the origins of zero in Egyptian, Babylonian, Mayan and Indian cultures. It touches on Medieval and Shakespearean conceptions of nothingness to move into the contemporary, science based, understanding of the Vacuum. It surely is an fascinating read but for me Barrow's work was a little too abstract and detached from the ordinary people experiences. I am not that interested in looking for Nothing in the cosmic space while there is so much Nothing around us everyday. It seems like that human side of nothing is not only easier to capture but for me, personally, it's also more interesting to explore.

There are so many thinkg people do when they say they do nothing at all. One could even find advice on what to do if you have nothing to do! The list I found includes trying to swallow your own tongue (amusement potential: 1-2 minutes), pretending to be a car (amusement potential: 5-10 minutes) and trying not to think about penguins (amusement potential: 1-5 minutes). The last one is especially hard, because by trying too much, you remember what you were trying to avoid thinking of. If you try too little, you end up thinking about penguins anyway. It's amazing what you can come up with.

I have created an online survey asking people some tricky question about nothingness in their lives but in order to fully understand its findings I looked into the concept of Nothing in philosophy. I found a great video about Nothing by British philosopher Alan Watts, who claims that "Nothing is what brings something into contrast" and that "you can't have Something without Nothing". His idea and explanation isn't as confusing as you might think and you can watch the video without risking a headache.

Watts was famous for popularizing Eastern philosophical ideas in the West. Taoism was among his interests and in this video he used a term 'Tao' to describe the unity of Something and Nothing, the Form and the Void.

Joan Konner - the author of You Don’t Have to be Buddhist to Know Nothing: An Illustrious Collection of Thoughts on Naught - is another influential expert on nothingness. She claims that "the concept of Nothing, in Western thought, is a paradox. We simply cannot accept, no less conceive of, the paradoxical concept that 'Nothing exists'. (...) In the material world, which we inhabit, the very words 'Nothing exists' are a contradiction in terms, an oxymoron."

Konner agrees with Watts that Nothing can and does co-exist with Everything, because everything, even in physical terms, has its equal and opposite. She says: "If a vacuum occurs, nature rushes in to fill it. But where and what would Nature rush in to fill if there wasn’t a vacuum? Without Emptiness there would be no opportunity for something new, or something else, to occur. Where would Something happen? Stars disappearing. Novas appearing. Leaves falling. New leaves growing. One generation dying, another being born. Nothing is the still center of the wheel of life. Nothing is the core of creation. In the dark evanescence between equal and opposite, the Universe ignites."

Maybe, that's the key to understanding nothingness? We can only capture Nothing by capturing the contrast to Something?

Nothing is invisible and, as John Lloyd argues, all the best things are invisible. Watch this very entertaining video to uncover what exactly he means by that.

And finally, I just wanted to share this last piece of research.

In June 2007 Discover Magazine published a list of 20 things that you didn't know about Nothing. And guess what! There is vastly more Nothing than Something. Roughly 74 per cent of the universe is “Nothing,” or what physicists call dark energy; 22 per cent is dark matter, particles we cannot see. Only 4 per cent is baryonic matter, the stuff we call Something!

Thursday 25 February 2010

Gripping on Nothing: Research Into the Concept of Nothingness

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

18:45

Introduction to Nothingology: Design Project B Outline and Workplan

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

17:17

Nothing doesn’t exist. Nothing is impossible. The concept of nothing is so fraught with paradox and contradictions that it defeats definition. We are surrounded by loads of nothing although we cannot come to terms with the concept. We do nothing, know nothing, hear nothing, have nothing, mean nothing, think nothing. And yet, we can’t define it or describe it. Nothingness is all around us even though we don’t seem to notice or understand it.

Writing a book about nothing contradicts itself. How can one focus on nothing, research, describe and illustrate something that doesn’t exist. Wouldn't a blank page express the idea better than any written word? Wouldn't the book's nonexistence communicate the idea most effectively?

Every attempt to discover nothing reveals yet another ‘thing’ – something smaller than the smallest, microscopic, unnoticeable because of its size or (non)importance. Probably, there is no nothing! Probably, nothing is always something!

This book aims to explore the idea of nothingness and to reveal the nonexistence, triviality, nonentity and nonbeing of surrounding us objects and pointless actions we take everyday. Its purpose is to uncover the real thing in nothing and to transform nothing into something.

This book takes a human-centered approach to nothingology. It will examine the complex interaction between people and nothing. What people do when they do nothing? What they think about when they think about nothing? What they say and hear when they say and hear nothing? And finally, what does nothing do to people?

In my design authorship project I aim to take the concept of nothingness on the journey through people’s lives. I don’t intend to simply reproduce the words of philosophers, scientists, poets and other experts on nothingness. I wish to express the idea with the words of ordinary people and support it with their real life stories. My aim is to communicate the concept of nothingness through typography, illustration and conceptual publishing solutions. And since there is no beginning and the end to nothingness, my book will have no beginning and no end, no page numbers and no cover.

You can contribute to my research by completing an online questionnaire – the survey of nothing.

Project Workplan

Click on the image to see a large version.

Monday 22 February 2010

TASK 3: Movements in Motion: A Guide to the Animated Digital Media Design

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

06:35

Desktop Digital Revolution and the Birth of Onedotzero

Year 1996. New desktop digital filmmaking tools are becoming available. It’s the beginning of the desktop digital revolution – a dawn of a new era in new media and motion design. A writer and former film critic Matt Hanson creates a film festival designed to showcase the vibrant new media collectives and digital arts scene burgeoning in London. Onedotzero is born. The festival becomes a platform to explore innovative moving image, live audiovisual performances, interaction design, computer gaming visuals, music videos, commercials in film and arts contexts.

Year 2009. After touring Buenos Aires, Argentina, New York, France and Russia Onedotzero festival returns to the BFI in London to once again amaze us with groundbreaking and inspiring works. “Decode: Digital Design Sensations”, which Onedotzero co-curates with the V&A Museum, showcases the latest developments in digital and interactive design from small screen based graphics to large-scale installations. The exhibition includes 35 works by established international artists and designers including Daniel Brown, Golan Levin and Daniel Rozin as well as emerging designers such as Troika and Mehmet Akten.

The exhibition that we saw in January 2010 certainly helped me to understand the today’s “computer-generated world of animated digital design”.

Quest for the Pioneers

The history of animation goes back to palaeolithic cave paintings, where animals are depicted with multiple sets of legs in superimposed positions, clearly attempting to convey the perception of motion. Other examples include a 5,200-year old earthen bowl found in Iran in Shahr-i Sokhta showing phases of a goat leaping up to nip at a tree and a 4,000 years old Egyptian mural with the images of wrestlers in action.

Motion design, however, has truly been developed only in the 20th century. It is being defined as a subset of graphic design that uses film, video or animation techniques.

Early examples include the typography and graphics used as the titles for a film, or opening sequences for television programs.

Among the precursors of the discipline you will find:

- Saul Bass – an American graphic designer and Academy Award-winning filmmaker known best for his design on animated motion picture title sequences. Amongst his most famous title sequences are the animated paper cut-out of a heroin addict's arm for Preminger's The Man with the Golden Arm, the text racing up and down what eventually becomes a high-angle shot of the United Nations building in Alfred Hitchcock's North by Northwest, and the disjointed text that raced together and was pulled apart for Psycho (1960).

- Maurice Binder - a famous title designer best known for his work on 14 James Bond films including the first, Dr. No (1962). Binder created the signature gun barrel sequence as well as the opening title credits, showing an artistic display of scantily clad and often discreetly naked females doing a variety of activities such as dancing, jumping on a trampoline, or shooting weapons. Both sequences are trademarks and staples of the James Bond films.

- Pablo Ferro - a director, editor and producer most famous for title design for Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Stop Making Sense (1984), Beetlejuice (1988), L.A. Confidential (1997) and Good Will Hunting (1997). Ferro is known as an early master of hand-drawn lettering, quick-cutting and for using multiple images within one frame. He received the DaimlerChrysler Design Award in 1999, and the Art Directors Hall of Fame Award in October 2000.

Animated digital media design, as we know it today, goes far beyond the title sequence design. Nowadays, about 12 minutes in every hour of broadcast television is the work of the motion graphics designer, yet it is known as the ‘invisible art’, as many viewers are unaware of this component of programming. Although this art form has been around for decades, it has taken quantum leaps forward in recent years, in terms of technical sophistication. The graphics, the typography, and the visual effects within this medium have become much more elaborate and sophisticated owing to the extensive use of computer graphics. The art of creating moving images via the use of computers is called ‘computer animation’.

Among the pioneers of the discipline you will find:

- Charles Csuri – the author of the first computer art (1964) recognized as the father of digital art and computer animation by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

- Donald P. Greenberg a leading innovator in computer graphics and the founding director of the NSF Center for Computer Graphics and Scientific Visualization. Greenberg has authored hundreds of articles and served as a teacher and mentor to many prominent computer graphic artists, animators, and researchers such as Robert L. Cook, Marc Levoy, and Wayne Lytle.

- A. Michael Noll - one of the first researchers to use a digital computer to create artistic patterns and to formalize the use of random processes in the creation of visual arts. He began creating digital computer art in 1962, making him one of the earliest digital computer artists.

Today, we are seeing stunning examples of computer animation in the most unexpected places. Creative new ideas are being applied Web design, architecture, engineering, interior design, landscape design and city planning. In healthcare computer animation is being used to demonstrate bodily functions and processes. Educators of all types are using computer animated programs as visual teaching aides. Students benefit from interactive learning, and from realistic graphic depictions of their subject matter. Artists who work in all media utilize computer animation to plan, create, construct and promote their works. Even make-up artists are delving into the high-tech computer animated field to advance their creative visions. More importantly, computer animation has had a huge impact on commercial advertising. New computerized billboards have appeared along highways that feature creative animation and design.

While researching contemporary motion graphic designers, I came across Jon S. Krasner's (2004) book titled Motion Graphic Design & Fine Art Animation: Principles and Practice, in which the author lists the key players in the field. I shortened his list to a few of my favourits.

- Viewpoint Creative – a team of producers, writers, designers and editors specializing in advertising and promotional solutions, such as broadcast logo and identity design, main titles, program packaging, DVD menus and interface design. Their clients list includes Discovery Channel, Animal Planet, Disney Entertainment, History Channel, Sci Fi Channel and the Travel Channel.

- David Carson – a film and television motion graphic designer with a special interest in commercials and music videos. “His intuitive use of images and typography (…) is expressive, experimental and multilayered. He reinforces content with form, and his use of subtle shape and colour contrasts communicates the feeling of the subject matter, often eliciting an emotional response from the viewer” (p.79).

- Big Blue Dot – a kid-oriented broadcast design firm with Disney, ABC, Microsoft and the Cartoon Network among the clients.

- Hatmaker – a design studio that serves the entertainment industry with a strong focus in broadcast design. Hatmarket created Cosmopolitan Television’s branding to complement Cosmopolitan magazine. “The goal was to allow for magazine’s expansion worldwide by communicating a sense of ‘local flavour with universal cohesion’” (p.82).

- April Greiman – one of the first graphic designers to combine video images and bitmap typography on the Macintosh computer. “Her work is daring, depicting a digital fusion of photography, airbrushing, and typesetting and is characterized by complex layering and manipulation” (pp.85-86).

Firstly, there is the 3Dization. In the early 90’s there were no true 3D games at all. Now a 2D game is an exception from the general rule. The 3D-craze is penetrating not only gaming world and cinematography (both animated and non-animated films come in 3D now) but seems to progress to broadcast as well. We saw a first 3D football game recently so the question isn’t if but when we start watching all TV programming with the funny glasses on. Since 3D models, used previously in games, are now being utilized in movies, footage doesn’t have to be rendered in real-time. Shortly only experts will be able to see the difference between a real-time video footage and pre-rendered graphics.

Photorealism of course goes hand in hand with 3D-craze because the point is to make a computer-generated graphic look like they were real.

Interactivity is another undeniable trend. User-controlled, web-based computer animations and motion graphics provide customized viewing experience. But it doesn’t end there. We can now enjoy interactive movie trailers (for example, Avatar) featuring interviews with the actors and designers involved in the production. But we can also participate in an interactive crowd gaming experience. In summer 2007 during the opening weekend of Spider Man 3 in Los Angeles moviegoers became a crowd of human joysticks.

The idea has obviously a vast potential in cinema advertising that was used in Sao Paulo’s Dove Bubbles Campaign. And the trend develops rapidly. Interactive motion graphics were used for car projection, for instance. A real 3D object (a car) was combined with digital virtual reality to create 'mixed reality' or 'augmented reality'.

However, it’s the live performance from the Sancho Plan during Thinking Digital 2009 that really shook the ground of interactive entertainment of 21st century. A live band performed in front of large screens. The on-stage musicians orchestrated sounds simultaneously controlling the on screen animated character. Truly spectacular. Sancho Plan is an award-winning collaboration of writers, musicians, animators, designers and computer programmers that create new interactive entertainment experiences by fusing animation, music, gaming, technology and performance.

- 3D flying graffiti arrows

- Pixiliation

- Ink Splatter

- Subtle 2D and 3D juxtapositions

- Light Rays

- One colour over B&W

- Digital-aided emulations of preexisting techniques, such as the return to the hand-drawn animation or dusting the style of the old movie title sequences.

- and my personal favourite - architecturally animated typography. As an example I share a video created by Antione Bardou-Jacquet for the French DJ Alex Gopher. A world made only with typographics. Cult video for font lovers. Enjoy.

Endnotes

I am aware that this post was extremely long but I just got carried away with the research. It was such an diverse and interesting topic. I hope you will find my post useful and inspiring.

Here are some additional links to motion graphics resources:

- Creativeleague.com - Directory of companies and individuals in motion design.

- Motionographer - A resource for some of the best works.

- MGFest: The Motion Graphics Festival - Touring festival of motion graphics screenings and education.

- Jerwood Moving Image Awards - A major new prize for artists working in digital moving art.

- The Mograph Wiki - a comprehensive wiki maintained by motion graphics professionals and fans.

- Mograph.net - A forum for discussion and advice on all things motion graphics.

- Onedotzero - A contemporary, digital arts organisation with a remit to promote innovation across all forms of moving image and motion arts.

Wednesday 17 February 2010

Coverline Design Company Concept

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

15:33

Who are we?

Coverline Design is a design consultancy specializing in magazine launching and redesign. We offer a broad multi-disciplinary expertise in developing a strong editorial voice, ultra-contemporary look and feel, broad readerships and efficient workflow for periodical publications.

We do understand that magazines are collaborative enterprises. Launching or redesigning a publication must emerge from a shared vision that incorporates editorial, design and business interests.

We realize that an in-house design can be a struggle, requiring not just talent and motivation but also initiative and energy. It means finding extra time within a regular production schedule to reimagine a magazine. It means finding a new visual vocabulary that is different from the one you speak daily.

Coverline Design translates those management, editorial and design concerns into a functioning structure. We recognize that even magazines with similar readerships can have very different souls. We respect and advocate the essence, the attitude and the personality of every publication.

What do we offer?

Depending on your publication needs, Coverline Design offers three major redesign services:

1. Updating – improved look without a change in content:

- changing the look and feel of the magazine without modifying the editorial voice and character of the publication;

- gradual updating of the particular design elements;

- a refreshing of the title rather than an extreme makeover (change in colour palette, signage, typography, image style, logo, cover, etc.);

- making the content more inviting, more accessible and revitalized in order to recapture advertiser or readers who have drifted off;

- reordering a format that has become unwieldy or ineffective in places;

- introducing new ways of presenting information.

- changing not just the physical form of the publication but who is reading it as well.

While the third and most severe stage of redesign might seem risky, for some publications it is a matter of life and death. If a magazine has covered a topic that no longer resonates with a sustainable readership, then it must expand or change its topic. If a readership is aging with the magazine, new readers must eventually be found. Turning-off old readers is a calculated decision taken to attract new enthusiastic readers of a different age or income level.

Coverline Design understands that magazines are carefully balanced ecosystems, and it can be hard to make minor adjustments without setting off a cascade of visual issues. Therefore, we always seek to establish authority and build consensus for a redesign.

When do you need a redesign?

We live in the age of tremendous change, many readers lose interest in a publication that looks as though it is standing still. In the past most magazines needed a redesign every seven years. Now, large newsstand titles seem to change every three or four years. And, if they are aimed at young audiences, two years is a norm.

The credit (or the blame) for this quickening of the redesign circle goes to the Web. The Internet has raised the overall level of visual literacy and created an expectation for freshness among readers. Magazines must run to stay in place.

Coverline Design recognizes the importance of regular, well-executed redesign and offers the expertise in both editorial management and graphic design to deliver successful design solutions when:

- Your editorial message has changed;

- Your audience has changed;

- Your staff has changed;

- Your production and distribution methods have changed;

- Readers attitudes changed;

- Advertiser attitudes changed;

- Your competition has changed.

Tuesday 16 February 2010

TASK 2: Which Way is the Wayfinding Going?

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

10:40

Retrospective

Wayfinding encompasses all of the ways in which people orient themselves in physical space and navigate from place to place. The term is being used in the context of architecture to refer to the user experience of orientation and choosing a path within the built environment, and it also refers to the set of architectural and/or design elements that aid orientation.

According to David Gibson (2009), three writers are largely responsible for popularizing the term wayfinding. In 1960, an urban planner Kevin Lynch explained the term in his landmark book, The Image of the City, as the process of forming a mental picture of one's surroundings based on sensation and memory. The subject was than explored further in Wayfinding in Architecture by Romedi Passini and Wayfinding: People, Signs, and Architecture, which Passini coauthored with Paul Arthur in 1992.

In addition to coining the term signage, Arthur also developed innovative wayfinding projects and eventually became a fellow of the Society for Environmental Graphic Design (SEGD), which today serves architects, planners, graphic designers, exhibition designers, product and interior designers who practice wayfinding. The SEGD annual competitions and website recognize outstanding achievements and innovation within the field.

Over time, environmental graphic design became the preferred umbrella term to describe any communications intended for spatial application, ranging from wayfinding sign programs to branded spaces, exhibitions, and even public art.

Trends

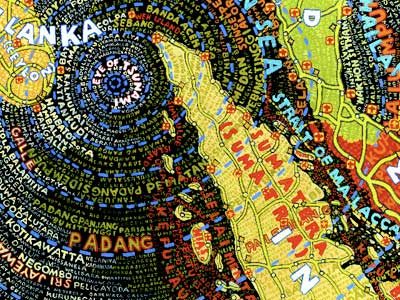

Just like any other aspect of design, wayfing is a subject to trends and fashions. Contemporary wayfinding design tends to be bigger and bolder than before. Tiny signs and arrows are often replaced with oversized typography placed on walls, floors and even ceilings. Letters and signs are sometimes distorted to fit the space. In 2006 Paula Scher and her collegues at Pentagram used the method in the design for Bloomberg L.P. Corporate Headquarters in New York. The project won the SEGD Honor Award. Two years later, Eureka Tower Carpark in Melbourne became another excellent example.

Just like any other aspect of design, wayfing is a subject to trends and fashions. Contemporary wayfinding design tends to be bigger and bolder than before. Tiny signs and arrows are often replaced with oversized typography placed on walls, floors and even ceilings. Letters and signs are sometimes distorted to fit the space. In 2006 Paula Scher and her collegues at Pentagram used the method in the design for Bloomberg L.P. Corporate Headquarters in New York. The project won the SEGD Honor Award. Two years later, Eureka Tower Carpark in Melbourne became another excellent example.However, according to Mark VanderKlipp (2007), “one of the hottest trends in wayfinding these days is interactive digital signage—the use of electronic kiosks and flat-panel screens that display instantly updated information of a user's choice”. As price points for LCD and plasma display technologies have come down in the last several years, digital signage has grown in prominence. Still, the channel remains young, its borders not entirely defined, and its potential vast (Frankel 2009).

Regardless of the designer's preferred materials and means of communication, a good signage design not only helps to navigate through the environment, but also represents a brand and communicates the host's intended messages. An inspiring example of such practice is a BrandCulture Communications design for Mirvac WA.

Concept Innovation, Strengths and Weaknesses

BrandCulture is an Australian design company specializing in creating branded environments and visual communications for retail, corporate headquarters, office and multi-residential developments.

The Mirvac WA brief was to differentiate the environment to reflect the local culture and independence that Perth has within Australia and consider a new way to reflect the ‘living line’ and brand values.

The ‘living line’ concept had been used in the Sydney office to great effect and again formed the backbone to this branded environment albeit in an edgier, more graphic form. The ‘living line’ starts in the reception and leads through the office across tiled and carpeted floors traversing walls, wooden beams and glass meeting rooms to ceiling tiles and down pin boards creating a sense of connectivity as well as guiding visitors through the building.

Rooms are subtly numbered using gloss grphic finishes applied to the matt painted walls and across the glass doors. The line connects all of the meeting rooms and spaces, each named after a landmark project. The names are inlaid into he the carpets outside the meeting rooms.

Graphics across the 30 meters of office ceiling highlight satellite meeting areas and connect the space with the main meeting rooms. They also help to navigate through this large space without walls.

The 'living line' interact with the brand values, which are laser cut into the red anodised aluminium beams laid into the pin boards. This has been designed to introduce the company values to visitors and to reinforce the company's identity.

Monday 15 February 2010

TASK 1: Comparison and Analysis of Two Chosen Typefaces

Posted by

Katarzyna Matuszewska

05:33

Helvetica (2007), produced and directed by Gary Hustwit, is a famous documentary about typography, graphic design and global visual culture, which looks at the proliferation of one typeface as a part of a larger conversations about the way type affects our lives. Following the screening of the film, I was asked to select and analyze two typefaces discussing the designers influences and the fonts' characteristics, strengths and weaknesses. I chose a modern slab serif typeface called Clarendone that seems to regain its original popularity in a very different post-modern environment as well as an extremely elegant and contemporary sans serif Kozuka Gothic Pro.

Clarendon is a slab-serif typeface that was created in England by Robert Besley for the Fann Street Foundry in 1845. Clarendon is considered the first registered typeface, with the original matrices and punches remaining at Stephenson Blake and later residing at the Type Museum, London. It was revised by Hermann Eidenbenz in 1953.

The font design was influenced by common wanted posters in American Old West as well as the government proclamations of the German Empire during the World War I.

Until recently, Clarendon Bold was used on a U.S. National Park Service signs. In 2008, the typeface was utilized extensively by the Ruby Tuesday restaurant chain in the re-launch of their corporate identity. The same year the font was used by the Norwich Union building society in rebranding exercise. Clarendon can also be seen in the logotypes of corporations such as Sony, Pitchfork Media, and Wells Fargo.

Clarendon is classified as a slab serif font which hybridize the bold presentation of a sans-serif and the horizontal stress of a serif face, characterized by an overall consistency in stroke weight. The serifs and the stems are of a similar weight. The body of a slab serif is often wider than what is considered normal.

Clarendon is a dynamic typeface full of contrasts. It can be distinguished by a contrast between angular serifs and round terminals (for example: r, g, a, y). There is also a contrast within a single stroke - flaring in thickness from the middle point of the stem outwards to the terminal (modulation). The speed of transition between thicker and thinner strokes (ductus) is rather vigorous making the typeface feel more active and energetic. The angular and rigid serifs contrast also with elliptical eyes and curvy bowls and shoulders.

Claredon’s joints are rather smooth with curves flowing into the stems with slow ductus giving the face slightly more relaxed and casual feel.

The relatively small x-height, shallow descenders and small counters give the face condensed, yet bold and legible feeling.

According to Return of the Serif by Scott Billings (Design Week January 2009) slab serifs are returning as a trend in magazines and newspapers. In 2005 The Guardian’s redesign led to the iconic Helvetica headers being replaced with slab serif font Guardian Egyptian.

Most serif typefaces are being redesigned to be used in display and advertising. Serifs now are much bolder and “in-your-face” even thought they are still traditional in some ways.

About Me

- Katarzyna Matuszewska

- I grew up in a small town in Poland believing that the only boundaries that should not be crossed were those which I set up for myself. Now, living in the cultural blur of a cosmopolitan city I stick to that rule. I cross boundaries between cultures, languages, between print and web, between journalism and design in search of original creative fusions. I graduated from University of Westminster in 2010 with a Masters Degree with Distinction in Design for Communication. I also hold a First Class BA in Journalism with Media and Cultural Studies from Kingston University, which gives me a combined knowledge of editorial and design practices. Having previously worked for The Sunday Times Magazine, Haymarket and Think Publishing, I have experience in publishing and design industries and a strong passion for editorial design. I am a great (bilingual) communicator, a competent writer and a designer. I produce imaginative magazine layouts to convey the publication‘s editorial mission and specialise in magazine launch and redesign projects. If you think your organisation could benefit from my knowledge and experience, please get in touch.

Followers

Labels

- Advertising (1)

- Book Design (7)

- Business for Design (8)

- Colour (2)

- Community (7)

- Critical Debates in Design (9)

- Design Authorship (8)

- Design Inspirations (1)

- Design Project B (7)

- Design Research Methods (8)

- Environment (5)

- Ethics (5)

- Honeycomb (3)

- Interactivity (7)

- Logo (4)

- Market Research (3)

- Master Project (1)

- Personal Projects (1)

- Printing (1)

- Project Brief (4)

- Redesign (1)

- RSA (24)

- Tasks (17)

- Touch Screen (11)

- Typography (3)